When it comes to tech startups and entrepreneurs in Alberta, David Edmonds is the man with the plan, network, and know-how. Check out the story behind one of the original tech “influencers”.

What can you tell me about your entrepreneurial story?

Well, you’re getting into prehistoric times [laughs]. When I graduated from school, I got hired by National Cash Register (NCR), and that August I was sent to NCR’s University in the U.S. I was sent away until Christmas Eve — to learn how to stand up, sit down, what to say when a customer yells at you and all those sorts of things. When I left for the U.S., the average age of employees at the company was 57. When I came back a few months later, it was 29. They’d put a salary cap on salespeople, so anybody who knew how to sell, left the company.

“I was on the team that sold the first banking machines to Bank of Montreal, sold the first electronic cash registers to Robinson’s, and introduced microfiche to all the banks in Toronto.”

So I pretty much had my choice of any job in the company that was customer-facing. It was a lot of fun, though it was fairly stressful because there weren’t a lot of senior people who could teach you. But I was on the team that sold the first banking machines to Bank of Montreal, sold the first electronic cash registers to Robinson’s, introduced microfiche to all the banks in Toronto, and then opened data centres across Canada.

After that, I couldn’t go back and just do a normal job because I was a “technology specialist”. I worked for them for, I think seven years. And it was good. I won top salesman every year and then the last year, top manager. I figured I was pretty hot stuff, so I thought I’d take a risk and went to System House — which was system integration and consulting — and worked on an iceberg system for Dome Petroleum iceberg identification. Unfortunately the company got in financial trouble and I got laid off, so I went to work for Computer Land and sold the very first PC in Calgary. And then ended up as Vice President of Sales Computerland/Computer Innovation.

That’s an impressive start, not to mention working your way up the tech chain.

Well then I started my own companies. I started a computer rental company focused on high-end engineering workstations. And those were, I thought, really big deals…until you realize they’re not. But it was a good training ground. Then I started a retail store because PCs were taking off. And I realized there’s a lot of money in it, but managing inventory stuff was tough, so I ended up selling the corporation. We became the largest software reseller and integrator in Western Canada for Lotus Notes and a few of the other products that needed customization. Sold that.

Then my buddies phoned me and said they wanted to start a company to compete against some of the big engineering workstation companies and become the dealer for Silicon Graphics, and that’s when we started Burntsand. And that evolved from a hardware integrator into a consulting company, into a software development firm. Took it public in Alberta then took it public on the Toronto Stock Exchange. We had just under 500 employees and 10 cities in North America and I think $60M in revenue.

And then I left, but in 2000 when the crash happened, I went back. My recommendation, I hate to say it, was to lay off 300 people because we had about $30M in cash. The Board said, no, they weren’t going to do it. So I said, well, I know you don’t want me on the Board because I disagreed. Ultimately it was sold to Open Text.

After that I invested in a company with Shawn Abbott and Randy Coates, and Randy and I took over Operations. So the good news is, my only failure occurred when the financial impact didn’t matter as much to my personal finances as it could have since it was later in my career. I eventually left there, and then Randy kept running it for another two and a half years and had a sale lined up to Xerox and the banks called the notes. So that wrapped that up.

I was an entrepreneur in residence at Innovate Calgary for a year. That’s where I learned about metabolomics, cancer research, veterinary science, nanotechnology and a few others. One of the things we did was we spun out a nanotechnology company. Then the downturn hit and we were able to survive through government grants, because of the research. And so we did a refinancing. Actually, Tim Hodge and I — his partners and my partners — we did a refinancing. It’s still running, and I think we’ve got probably the three smartest people in the world working on it.

After that, well I’ve been doing what I do right now ever since. I did it for 10 years for nothing, and then somebody said they’d pay me to do what I do. So I said, I’m not that bright, but I figure that’s probably a good way to do it [laughs].

That is quite the fascinating journey. At what point along the way did you decide you wanted to go do your own thing? What was the catalyst for that?

I had been offered to take over the role of Vice President in Toronto for Computer Innovations. I turned it down, twice. I think Sarah, my youngest daughter, had just been born. Joy, my wife, and I talked about it and I said, there’s no way I want to move back East. They asked me one more time and I just said, no. And they said, well, we can’t keep you in that role because you’re making more money than anybody else in that job category. So I just said, okay, well, I’ll go do my own thing, which was a company called Soft Option — the retail store and enterprise sales and software development — which we purchased out of bankruptcy.

“I was just tired of people telling me what to do. That was why I came West.”

I was just tired of people telling me what to do. That was why I came West to begin with, because my boss promised me he wouldn’t bug me. So for five years at NCR, I had him as a boss, but as long as I hit my numbers he never called. We had a symbiotic relationship that way [laughs].

As you said, this was in the early days of tech. Were there other tech firms that inspired you to pursue your own gig in that space?

We started Burntsand here in Calgary, and I’ll tell you that story. There was a big event in Silicon Valley, and Jim Clark, the guy who founded Silicon Graphics, was giving a speech and we had a table with bottle service, a bottle of scotch. And he said, “I don’t know why people get excited about technology, it’s nothing but burnt sand.” So, we flew back and trademarked and registered the name. That’s how we came up with the name — scotch and a speech [laughs].

“I could name 20 of the tech companies back then and we ran them like an oil company, which was, you tell no one what you’re doing. And you show no weakness.”

Anyway, when there were tech companies at that time, the majority were like Brian Craig’s company, which were engineering/energy-focused in some form. And there was a lot of them — Stephen Kenny, he had his company, Brad Zumwalt had his company. You know, Pat Lor and Bryan de Lottinville at Benevity, they all worked with Brad.

What was interesting at that stage was, I could name 20 of the tech companies back then and we ran them like an oil company, which was, you tell no one what you’re doing. You share nothing with anybody. And you show no weakness. So rather than a collaborative environment, we all worked on our own. So I didn’t really get to know Brad until the A100 was formed. Same with Brad Johns. Because of what I was doing in the community, when people were looking for a job or wanted advice — like Terry Sydoryk or Rod Charko who started Alberta Enterprise — I was kind of like the biz dev connector. So I’d gotten to know them, but not a lot of the big exit folks.

So we knew who each other were for the most part, but there was very little interaction, especially in the late ‘80s, early ‘90s.

“Many companies were started here because of others seeing the success folks like Brian Craig, Ray Muzyka, Brad Zumwalt, Stephen Kenny, Cory Janssen, etc. had here in Alberta.”

But you know, when talking with Absorb LMS founders Mike (Owens) and Mike (Eggermont), they told me they saw that you could start a tech company in Calgary, like Burntsand, and make it successful. They felt they could do the same with Absorb. That’s what having peers and role model comparables in the community can do. I expect many companies were started here because of others seeing the success folks like Brian Craig, Ray Muzyka, Brad Zumwalt, Stephen Kenny, Cory Janssen, etc. had here in Alberta.

Since we’re talking about the A100, how do you see the 100 impacting Alberta’s startups?

Well, I know we’re having an impact. You know, I look at our member network diagram, and on every committee, on all the panels, there are A100 members. My belief is you can have more impact on a quiet influence level than you can have being noisy, waving your arms.

“When I look at Jobber, Clio, Showbie and Scope AR, I know for a fact upwards of 10 or 12 A100 members have met with all of those companies through the phases of their growth.”

It’s like enterprise sales. You find out who’s got the money, who’s got the time, and until that person’s committed, you’re just down low and figure out who the other influences are, and they go out and propagate. So when you win the $25M deal they go, how the hell did that happen? I know for a fact I’ve touched more than 700 companies in the 10 years I’ve been doing this. And that’s not meeting 700 people, but that have been identified, have done from follow up, and so on. When I look at Jobber, Clio, Showbie and Scope AR, I know for a fact upwards of 10 or 12 A100 members have met with all of those companies through the phases of their growth. So for me, that’s fantastic.

Speaking of those companies and their growth, what have you learned from your successes?

I think the first thing is, you’ve got to have skin like a rhinoceros. Everybody’s going to tell you no, you’re an idiot, that can’t be done — all those negative things. We talk about fast failure — it’s a hard thing to separate because you got to prepare yourself to have all these people tell you you’re wrong, and not give you the support. But you also have to have the resilience to continue to maneuver to get to a point where you get product-market fit. And really, until you get that, you’re going to get a lot of no’s.

You know, my whole career, because I’m incorrigible, when somebody told me it wasn’t possible — like a nanoparticle fluid we developed, they said it couldn’t be done — to me that was fantastic. Because that means if we pull it off, we’re going to make a lot of money.

“Because I’m incorrigible, when somebody told me it wasn’t possible, to me that was fantastic. Because that means if we pull it off, we’re going to make a lot of money.”

So that’s one. I think the biggest thing that I’m proud of with the A100 is, they’re all giving back to new entrepreneurs. Which to me, that’s the way that you create a strong, resilient, grassroots tech community. So, be open to working with others who’ve already gone down the path.

Then the other side of that coin: the failures. if any, what have you learned? And how would you counsel others on how to cope with failure?

So at Preo, we had a lot of challenges. But when I was down south, I gave a presentation to the senior executives at Lexmark. They said, look, we think we want to buy you guys. I flew back and the Board — very good Board members — said, nope. Nope, we can’t do that. It’s a way for them to try and buy the company on the cheap. And I said, well, I don’t think that’s true, because our corporate sponsor — who was the first female VP there — I said, I know her really well. And it was no, you can’t talk to them, we gotta wait for them. And the long and the short of it was, the deal fell apart. And our sponsor, the VP, she got fired.

“As a CEO, whoever your advisors/board/coaches are, you have to listen. And whether you do it or not isn’t as important as how you respond to it.”

Now, I don’t have many people who hate me, but I think maybe she might be one because it cost her career. My whole point there is, as CEO, you’ve got to listen to your Board. But rather than capitulate, I should have come back with data supporting the reasons why I believe that we should have been done a mutual acquisition rather than try and play hardball. So I think, I think as a CEO, whoever your advisors/board/coaches are, you have to listen. And whether you do it or not isn’t as important as how you respond to it. Saying, I heard you, but from my experience and what I’m seeing in the market, this is what I see. Do you see any holes in that argument, other than emotions? Because that’s the biggest problem, emotion. So, having the resilience and the wherewithal to listen, process that, and come back with a yes or no to those advisors.

Sound advice. I’m going to ask you for your book recommendations now, if you have any. What book has had the greatest influence on you so far?

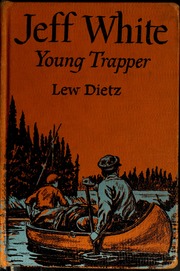

I read a couple of books a week. But I primarily read fiction, just because it allows me to cleanse my head. I read a book when I was a little kid called, “Jeff White, Young Trapper”. It was about was this kid who had to learn to live on his own and navigate being lost in the wilderness. Since I still have the book, I’m looking forward to being able to read it to my grandson. All the lessons were about, when you’re faced with adversity, you what do you do? Do you give up and cry for your parents to rescue you? Or do you try and figure out a path that will get you out of that problem? I don’t think you’ll get anybody else telling you about a book they read when they’re seven or eight [laughs].